Python 3 Types in the Wild

Reviewed by Greg Wilson / 2022-03-18

Keywords: Programming Languages, Types

Python used to be the kind of language you could pick up in a couple of days, but "used to be" was many years ago. Coming back to developing products with it after 11 years away, I've been a little overwhelmed by how many features have been added, and how hard it is to make sense of a modern code base without understanding all of them.

One of the biggest changes has been the addition of type annotations,

which allow developers to say that a function returns

Dict[List[Set[FrozenSet[int]]], str]

(i.e., a dictionary that maps lists of sets of frozensets of integers onto strings).

RakAmnouykit2020 takes an empirical look at how programmers use these annotations,

and turns up some surprising results.

For one,

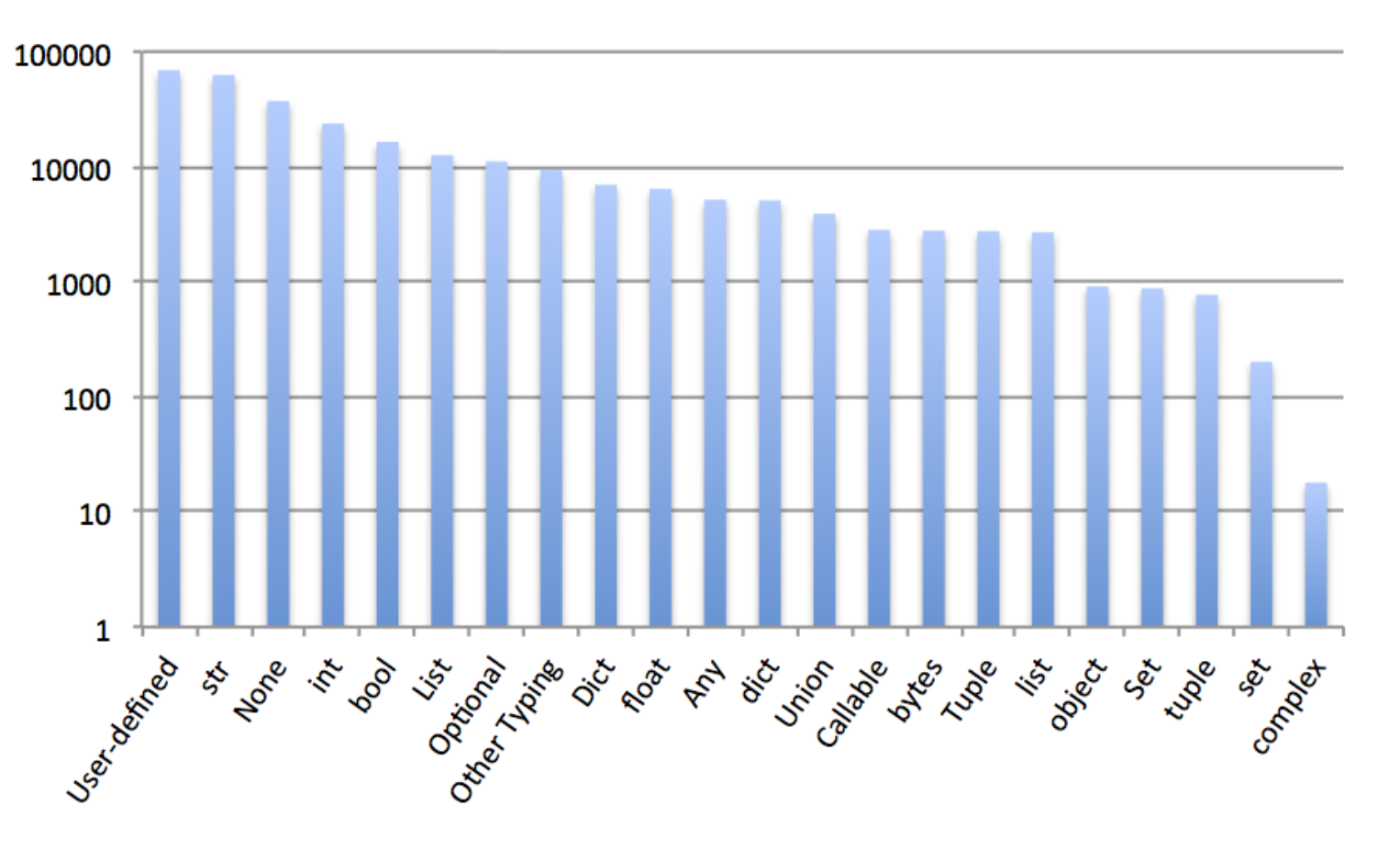

the most common kind of type annotation is a user-defined type:

What's more interesting is that when the authors stripped annotations out of files and asked PyType to infer them, it failed to do so in 77% of cases, which means that the user-written annotations were capturing information that automatic tools couldn't. On the other hand, MyPy found that only 15% of the 2,678 repositories examined were type-correct; this may be a result of MyPy being very conservative and producing false positives. More troubling are the disagreements between these different tools, but studies like these are exactly what we need to make those tools more consistent and more helpful.

RakAmnouykit2020 Ingkarat Rak-amnouykit, Daniel McCrevan, Ana Milanova, Martin Hirzel, and Julian Dolby: Python 3 types in the wild: a tale of two type systems. In Proc. ISDL 2020, doi:10.1145/3426422.3426981.

Python 3 is a highly dynamic language, but it has introduced a syntax for expressing types with PEP484. This paper ex- plores how developers use these type annotations, the type system semantics provided by type checking and inference tools, and the performance of these tools. We evaluate the types and tools on a corpus of public GitHub repositories. We review MyPy and PyType, two canonical static type checking and inference tools, and their distinct approaches to type analysis. We then address three research questions: (i) How often and in what ways do developers use Python 3 types? (ii) Which type errors do developers make? (iii) How do type errors from different tools compare? Surprisingly, when developers use static types, the code rarely type-checks with either of the tools. MyPy and PyType exhibit false positives, due to their static nature, but also flag many useful errors in our corpus. Lastly, MyPy and PyType embody two distinct type systems, flagging different errors in many cases. Understanding the usage of Python types can help guide tool-builders and researchers. Understanding the performance of popular tools can help increase the adoption of static types and tools by practitioners, ultimately leading to more correct and more robust Python code.